EGD News #148 — Industry life cycles in gaming

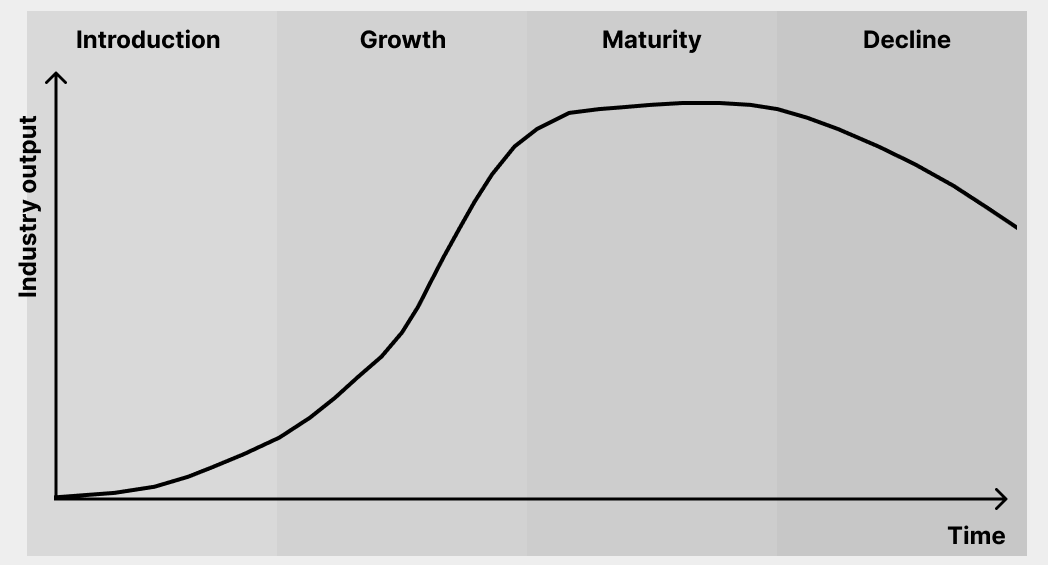

I love this concept of the industry life cycle. It makes timing the market in gaming much more understandable.

You start with the introduction phase, where an industry is introduced, and people experiment to see if there’s something there. Once the experiments reveal business sustainability, the industry moves to the growth stage, and everyone starts following the business model, the distribution model, and everything that is working.

Growth involves a lot of innovation, which only lasts for a while. Then we enter the maturity phase, where the big players become entrenched, and the business fundamentals have been figured out. Companies are getting acquired left and right.

Finally, the industry enters the decline phase, and people start to look for other places to make a buck.

Inside gaming, there are several ongoing life cycles. Each segment or platform has its own life cycle: PC, console, VR, and countless others. I will focus on how a few recent gaming platforms have gone through these life cycles.

Facebook gaming

Many of you remember Facebook gaming, which was also called social gaming. It was the first time that free-to-play was brought to the masses. These games started appearing once Facebook announced its canvas apps platform in 2007.

There were several early movers in creating these social games, where the critical business innovation was the aggressive utilization of Facebook’s social graph. Distribution was free; Facebook’s news feed and algorithms were in their infancy, and they were keen on bringing games on the platform, which would lead to Facebook having more engaging content for its users to stick around.

Where are we now with Facebook gaming? In early 2011, Facebook gaming peaked, with Zynga’s Cityville reaching 100 million monthly activities. Still, Facebook had already started to come to its decline stage. My first company was operating in social gaming when the decline started, so I saw it first hand.

There were a few reasons why Facebook entered the decline stages so fast:

In late 2010, Facebook had closed down the best viral growth features. You couldn’t spam your social network with messages from games; gaming messages were isolated under a Facebook gaming section. But no one was using the gaming section. People were discovering games through friends who suddenly stopped sending them messages from new cool games. Developers had to rely on ad spending to drive growth for their games. Since most games weren’t great at long-term retention, the LTV they could achieve was nowhere near as good to justify the ad spend.

The final nail to the coffin was the introduction of smartphones in the late 2000s. Eventually, people started to prefer mobile apps over desktop browsers. This switch didn’t happen overnight, but the decline was evident, and when you are in the business of growing, it was a decision for many game developers to pivot or to go to zero.

Mobile gaming

I recently listened to Joseph Kim’s phenomenal interview with Will Harbin, founder, and CEO of Global Worldwide, a spin-off from his previous company, Kixeye.

We had some incumbency syndrome, we thought, “Hey, where’s everyone going? The water’s fine. This is easy. We’re making so much money. We don’t need to do mobile.”

That was Will Harbin explaining why they missed the boat on mobile. They saw others rushing into mid-core mobile and decided to stay on Facebook desktop browser. It feels like something that many people are saying about staying in free-to-play in 2022. The water is fine! Or is it?

Let’s look at mobile through the lens of an industry life cycle.

Introduction phase. Smartphones came out, and Angry Birds was the first hit game. But it was a paid game, where you had to buy the game from the App Store. Rovio wasn’t alone. Lots of experimentation was going on, where developers would have a free version and a paid version out at the same time.

No big studio was yet out there. We had Cut the Rope, Temple Run, Fruit Ninja, and many others. It was hard to know what would happen. No one saw Clash of Clans, Candy Crush Saga, and others coming.

Growth phase. The big winners incorporated what they’d learned from Facebook gaming. Free-to-play eventually became the dominant business model for mobile games, solving distribution through a UA arbitrage where developers could bid higher on acquiring app installs through ads, as long as they knew that eventually, LTV would surpass the cost.

You had to look at LTV and CAC to start growing. People are coming back to the game for months and gradually spending more and more in the game. The growth phase, also called the “mobile tailwinds”, lasted from 2012 to approx. 2016, as many companies became huge. King, Supercell, Playrix, Peak, Kolibri, and many more. All of them realized the fundamentals of what worked on this new platform.

Maturity phase. By 2017, the growth had slowed down, and the “big players” in the industry had claimed their spots. As Investopedia states about the maturity phase, “Market share, cash flow, and profitability become the primary goals of the remaining companies now that growth is relatively less important.” New entrants are trying to play catch-up inside established genres, chasing the fads.

I’ve shared this quote before, but it hits the nail on mobile’s maturity phase. In March 2020, Paul Murphy spoke on my podcast. At the time, the crystallization of the maturity of mobile was evident.

I’m seeing a lot of companies that are, for lack of a better word, kind of doing the same thing. The strategy is [hyper] casual, casual to mid-core, or some version of, hey, we can build a better mousetrap and raise our LTV over time.

Decline phase. In the decline phase, the industry becomes nearly impossible for new entrants. Sure, you can have the outlier Tesla breaking into automotive or a Royal Match breaking into puzzle game charts on mobile. But I’d instead categorize Tesla as creating a new life cycle of battery-powered cars, and Royal Match building “a better mousetrap.”

Apple’s IDFA depreciation ensures mobile gaming is in the decline phase. It’s reminiscent of what Facebook did when they restricted access to the social graph: destroying distribution and incapacitating a thriving games business from existing on their platform.

Eric Seufert puts it well in a recent DoF podcast episode when talking about the struggles in mobile:

You have to Live ops treadmill and the UA treadmill. That UA treadmill… the strategy’s changed fundamentally. The live ops piece becomes much more important. And while people are still figuring out how to run UA at scale, now you have to emphasize the games you have, to live in the market that is not working.

Mobile developers learned what works in UA and Live ops. As UA is failing, players in the space are emphasizing live ops of their big games. Smaller ones, especially new entrants, might not have the option to stay in a declining industry.

What about Web3?

Many people tell me they’re not objecting to web3 and crypto gaming emerging. But they don’t see how it could be better to play their favorite games as a web3 version. The game is perfect, and the gameplay works.

I think it’s a bit like saying that “StarCraft” is brilliant; why would you ever want to play a mobile free-to-play version of that? Still, Clash of Clans became the most significant game that mobile ever saw, perhaps even the “great game” in terms of staying power, longevity, and financial success. Ten years old and still around, making hundreds of millions every year.

Mobile gaming was convenient for people. That’s why Clash of Clans became so big. You have a supercomputer in your pocket. You can use it whenever you’d want. The “great game” was there where ever you went.

We do not understand yet what the “great game” for web3 will look like. We are in the introduction phase of the industry life cycle. When we were in the same phase for Facebook gaming or mobile, we had no clue where it would lead. What would the “great game” look like, and whether it will be mass adoption?

Regarding mobile’s role in Web3, it’s a big unknown. Perhaps we are seeing the decline of free-to-play mobile and the emergence of web3 as a device-agnostic platform.

We’ve seen the first innings with Axie Infinity and STEPPN, but neither was a “great game,” especially since they didn’t have the staying power.

All the dialogue about web3, startups working on crypto gaming, and funding flowing into this new industry are benefiting the industry to move towards the growth stage. We are accelerating in the introduction phase, and the experiments will eventually give us the growth phase and the great games.