EGD News #129 — Founder dilution

Sent on December 3rd, 2021.

If you aren’t a subscriber to EGD News, you can subscribe here.

Founder dilution

I recently wrote a post on Linkedin about founder dilution. Founders are often extremely worried about dilution. When I did my first startup, I was extremely dilution sensitive, but I didn’t have as many pains from owning less of my company with my second startup.

Today’s piece will hopefully alleviate the pains of raising and diluting your ownership.

Here are ten things that founders often think about, and I try to explain the situation in a way where the worries about dilution could be less problematic.

1. Losing control

“I don’t want to give up control” Sure, but your investors will be there to build the company with you as partners. The investors want the company’s value to go up, not to run the business for you.

What I’ve observed in the past years, VCs don’t want to take control of companies. First, they would not be able to do more deals if they over-ruled founders. Second, it’s not their business model at all; they want to build an investment portfolio of companies and not to get extensively involved in one or two companies.

2. Not owning much at the exit

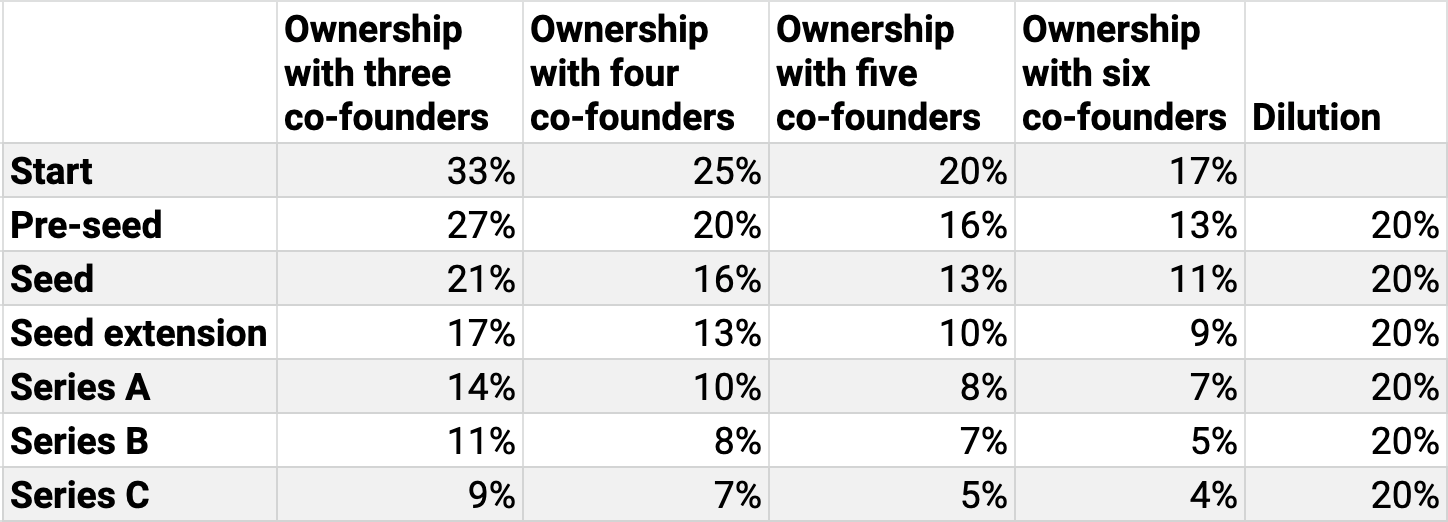

Almost all exits happen after three funding rounds of dilution. Each time you dilute 15%-25%, meaning that founders will have less than half of the company at exit.

Seeing your percentage in the company go from 20% to 15% to 10% to 5% can feel demotivating. All that hard work and as you progress, you own less and less of the company.

This is what happened us at Next Games: each co-founder owned a quarter of the company, and when the company was sold to Netflix, I had an ownership percentage of roughly 3%.

Instead of worrying about ownership, I was keener on how the company valuation and share price were developing with each subsequent funding round.

Having less percentage in the company doesn’t mean much, as long as you bring on capable VCs who will act as partners in building a great company.

To make this worry feel less harmful: since new shares are always created for new investors, existing investors will also dilute in rounds 2, 3, etc.

3. Raising ten rounds can feel bad

If each round takes the company to the next level, it won’t be bad. Funding is meant to take the company to the next stage. You have 1M shares; at a $1M valuation, it’s $1 per share. Raising again at a $5m valuation, and then again at a $20m valuation, you dilute to half the original ownership, but your share goes to $10-$15 per share.

As you go through the stages, you want to involve financiers who can help you get to the next stage. Pre-seed and seed investors, helping to get to Series A. Series A investors are helping to get to Series B, etc. If I were building a venture-backed company, I would pick my investors by asking: “How can you help me take the company to the next stage?”

This question doesn’t get asked, and I believe it’s got a lot to do with the founder’s sensitivity to dilution. The expectation is to get the funding and hopefully not raise again. You are constantly raising to go to the next level; that is the proven path to success for venture-backed companies.

4. Few founders are better than several ones.

Besides fundraising, founders are sensitive about bringing on several co-founders. The more co-founders you have, the more your share in the company will dilute.

If you had a split of 16.7% between six co-founders, you would own 4% of the company after six rounds. I’ve seen structures where you’d have two main co-founders who own 30% each, and then the leftover 40% is divided between four other co-founders, based on contribution, skill level, and how early or late into the founding process did they join.

For more on this, read my previous piece on co-founder equity splitting.

5. Showing enough traction is challenging.

The VC journey is as much about dilution as creating billion-dollar companies. The optimal VC journey would be the company that raises pre-seed, seed, Series A, B, and C, and then raises D at a few billion.

You are trying to get the highest valuation to get a minor dilution. The next round is much harder to raise since you need to show progress. It’s much easier to go from 800k to 3m than 3m to 11m.

6. Convertible notes make things (too) easy.

Yes, convertible notes have many things that they solve for early-stage companies. Less paperwork and legal costs for the early stage, and you can incentivize joiners with actual stock because no taxable valuation has been placed on the company, where giving out stocks would have a value.

But, at the same time, you are kicking the “dilution can” down the road. Keeping up with the ownership structure can be hard when doing several convertible notes at different stages with different valuation caps.

One day, when the notes convert, the founder might realize that they’ve given up 40% of the company as they signed notes and got easy cash into the company.

For more information, read my piece on convertible notes.

7. Venture debt financing

Venture debt seems like a great way to dilute less. But startups are challenging and often require additional funding. If the debt gets called by the financier during hard times, it could be disastrous in so many ways.

8. Project financing

If you are dilution sensitive, you will like project financing. It can be similarly challenging as raising from VC since you need to convince the backer that you have a solid business which is going to grow a lot with their financing.

Project financing brings capital for a certain project like a game that you are making, but often there is less help focused on building the company, which is what great VCs strive to do.

9. Web3 financing

In the past few years, several startups have set up a DAO, which issues tokens for investors. It’s like a mini-IPO, with tradable assets linked to the company’s performance but not connected to the company’s ownership.

I will explore the mechanics of DAO financing in a future piece.

10. Secondaries

It’s becoming more and more common for founders to sell some shares when they raise later-stage rounds. When a “secondary round” happens, investors buy existing shares from founders or other shareholders who are willing to share. Secondaries are pretty common at Series B and later stages, but I’ve seen this happen already at Series A, especially when to company starts to go beyond the $50m valuation point.

Secondaries are a great way to remove stress from the founders about taking significant risks and staying motivated. Usually, secondaries vary from $100k to a few million per founder, depending on the stage and other factors.

Conclusion

There you have it. Ten ways to think about founder dilution and possible remove misconceptions and unknowns. Dilution gets easier to accept as long as you understand the fundamentals of VC-backed startups, which is that VC is meant to take your company to the next level, and dilution is part of the game.

I’ll leave you with a comment from Henric Suuronen from Play Ventures:

(Photo by RODNAE Productions)

Get my book, “Long Term Game: How to build a video games company” from Amazon. Available on Kindle, audiobook and paperback.

Alex Arias and Andreas Risberg — Game devs going Web3

In this episode, I’m talking with the co-founders of Trailblazer Games, Alex Arias and Andreas Risberg. Trailblazer Games is a new web3 games company, founded in 2021 and recently they’ve announced a seed round of $8.2m raised from investors like Makers Fund and Play Ventures.

In this discussion, we talk about the founder’s background, how they both worked at King and brought learnings to their own startup, and what kind of games the founders are now building with blockchain technology.

Listen to the full episode by going here.

If you missed out on these

- Success in fundraising

- Deep work

- From operator to investor

- Confront the brutal facts

- Audio Ads in Games

- 80% proven, 20% innovation

- Put your investors to work

- Gaming in Africa

- and more

Articles worth reading

+ Seven Ways to Take Battle Passes to the Next Level — “Battle passes have quickly become one of the most differentiating features when comparing the top-grossing games to other mobile titles and can be almost seen as one of the core elements for a successful free-to-play title. In this post, we’ll explore some high-level data and the benefits of the Battle Pass but focus primarily on more unique and innovative ways to tailor the feature for specific cases and make it even more engaging for your players.”

+ Examination of web 3 gaming ‘guilds’: how they work — “Guilds were popularised by Yield Guild Games, who were the first to identify that there was a gap in the market between players who wanted to play and earn, but couldn’t afford to buy NFTs, versus investors who had capital or NFTs but lacked the time to play games.”

+ How to make a hit out of your casual game — “Hyperlite needed a different approach in UA, Monetization, and in-game metrics for Minesweeper. When the game first launched, it received 28.4k monthly installs, the retention of D1 was at 27.6%, and the LTV of D1 was $0.08. The gameplay needed improvements, so Homa Games’ team of UA, Monetization, ASO managers, Ad Creatives, and its N-testing in-house technology stepped in to help the studio work on these aspects.”

Quote that I’ve been thinking about

“Failure is our most important product.”

— Robert Wood Johnson, founder of Johnson & Johnson.

Sponsored by Audiomob

If you’re enjoying EGD News, I’d love it if you shared it with a friend or two. You can send them here to sign up. I try to make it one of the best emails you get each week, and I hope you’re enjoying it.

I hope you have a great weekend!

Joakim